In contrast to the self-absorbed protagonists who populate so many contemporary novels, Piranesi is completely unencumbered by questions of identity. For one thing, he has forgotten his real name for another, he doesn’t have the slightest interest in finding out what it is. It’s hard to say more about him without giving away too much, in part because he seems to know hardly anything about himself.

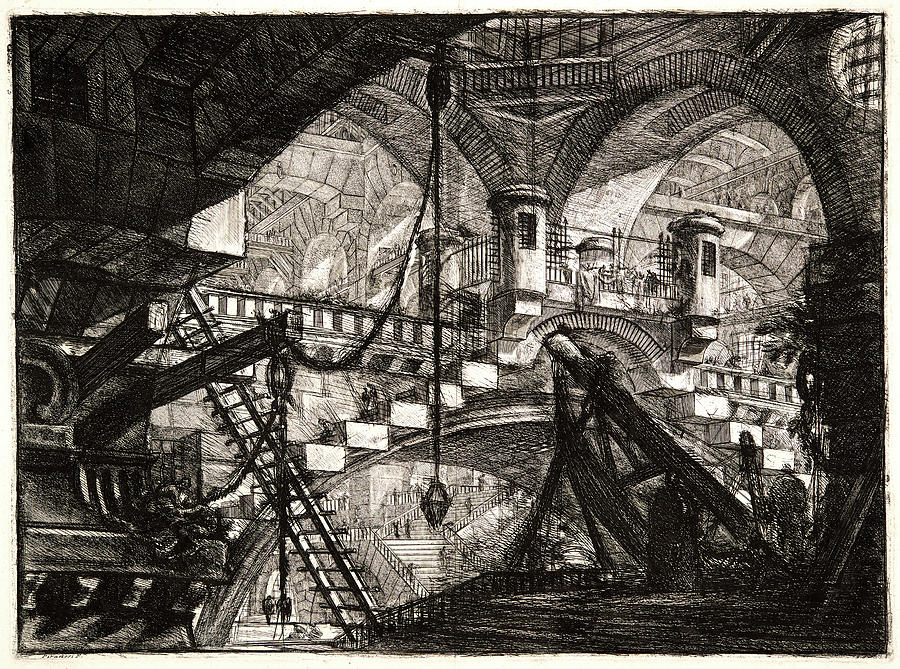

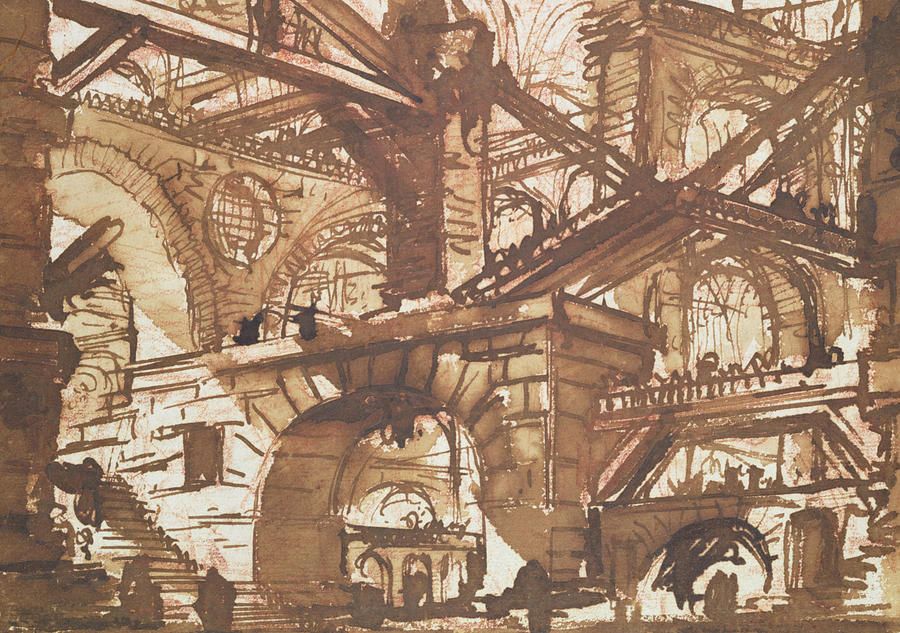

#Piranesi fanart series

She is one of those writers who use the tools of fantasy to talk to us about ourselves.”īoth timeless and strikingly timely, Piranesi takes the form of a series of journal entries written by a man who lives in a perpetual quarantine of sorts, an isolation so complete that he spends his days primarily speaking with birds and statues. “Susanna is part of this beautiful, very strange British literature tradition in which fantasy is one of the keystones and it’s neither privileged nor judged. When I spoke with Gaiman, he traced Clarke’s literary lineage not to Tolkien but to an older British genius: “It absolutely goes straight back to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, not to mention The Tempest,” he said. But if her first novel established her as one of the world’s best fantasy writers, Piranesi is set to place her in the pantheon of the greats, no modifier necessary. That slim volume, titled Piranesi, is not the sequel Clarke had once alluded to in interviews. His mind is a mystery - both to himself and to the reader. “There was the book - complete.” Piranesi is completely unencumbered by questions of identity. “It was the most extraordinary thing,” she said. “I remember thinking at the time it was as though she’d been captured into the land of Faerie,” Pringle told me, “as if she had been taken away from us.” And then, about a year ago, a dazzling manuscript unexpectedly arrived in Pringle’s in-box. Eventually, even Clarke’s communications with Pringle slowed.

At one of the author’s last public events, a conversation with Gaiman in 2007, her editor, Alexandra Pringle, noted how pale and otherworldly Clarke looked. In a smattering of conversations with journalists between 20, she mentioned that her work on the sequel was being delayed by an illness: She had been diagnosed with chronic-fatigue syndrome, and, as the years went by and her seclusion deepened, readers despaired that she would never publish another word. But just a few years after the book came out, Clarke withdrew from public life. Unable to explain their anguish, their isolation is total.Ĭlarke’s fans believed the book would elevate the fantasy genre to new heights of respectability and esteem, and indeed, Jonathan Strange was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize, becoming the first and only work to receive both a recognition from that prestigious institution and a Hugo Award, science fiction’s highest honor. Exhausted, these captives return to England every morning only to find that an enchantment prevents them from speaking of their suffering. But as the magicians gain power, a faerie steals their loved ones and brings them to a place called Lost-Hope, where they are forced to spend each night participating in dreary processions and ghostly balls. Those who master these magical arts can conjure wonders from their surroundings - works of poetry written in the land and sky. Writing in a voice that evokes Jane Austen’s, Clarke presented magic not as some pyrotechnic force, a bolt of light crackling from a wand, but as the language of trees and rain and the stones of old cathedrals, of all the mundane things that made up the pastoral landscape of a forgotten English past. Spanning nearly 800 footnote-laden pages, Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell tells the story of a pair of dueling magicians in Regency England who restore magic to the British Isles some 300 years after its abrupt disappearance. Her friend the fantasist Neil Gaiman later said that encountering her writing was akin to “watching someone sit down to play the piano for the first time, and she plays a sonata.” It was nearly 20 years ago that a first-time novelist named Susanna Clarke, then 44 years old and earning a living as an editor of cookbooks, finished writing what was perhaps the greatest and most original British work of fantasy published in England since the days of C. S. Lewis and J.R.R.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)